Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) is an artist who has been a motivational figure for me since I studied Fine Arts. What he did was ground breaking. It was inspirational. Now, having been lucky enough to have seen his retrospective at the Tate Modern, I see that his work was far more extensive and far reaching than I remember. What is striking is the curiosity, imagination and variety of his endless experiments — his sense of humour — his outlook on life and art.

Detail from Rauschenberg statement on Joseph Albers, undated. Courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

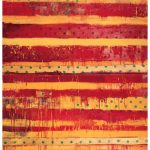

Having studied under Josef Albers at the avante garde Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Rauschenberg was exposed to the full range of diciplines and the expectation to explore them. He found Albers criticism “excruciating and devastating” but also considered him the most important teacher he ever had. This grounding seems a vital contribution to Rauschenberg seeing everything and trying everything. This is evident considering his white paintings, black paintings, red paintings, tire tread impressions, images recorded on light sensitve blueprint paper, transfer drawings, constructions using everyday materials, silk screen printing etc. etc.

- Untitled (double Rauschenberg) ca. 1950

- John Cage 1952

- Untitled 1953

- Yoicks 1954

- Canto XVIII: Dante’s Inferno Series 1959-60

Meeting John Cage and Merce Cunnungham at Black Mountain led to Rauschenberg doing the set and costume design when the Merce Cunningham Dance Company began in 1953. Through this work he become a player in performances as well. The innovative and aesthetic Pelican (1963) with Rauschenberg on roller skates donning a parachute or the experiment in propulsion using himself and two large rubber tires as seen in Map Room II confirm his creative interdiciplinary versatility. Collaboration remained an integral aspect throughout Rauschenberg’s career.

While set designing with Merce Cunningham, Rauschenberg also created combines. Combines, are neither sculpture nor painting, but rather works which incorporate aspect of both in constructed works. An early combine, collaboration and pivotal work was Short Circuit (1955).

“Rauschenberg was invited to participate in the Fourth Annual Painting and Sculpture Show at the Stable Gallery; some artists he wanted included were not. So Bob made a Combine – he called it Short Circuit – which incorporated works by the refusés: Jasper Johns and Bob’s former wife, Susan Weil.”

“Rauschenberg was invited to participate in the Fourth Annual Painting and Sculpture Show at the Stable Gallery; some artists he wanted included were not. So Bob made a Combine – he called it Short Circuit – which incorporated works by the refusés: Jasper Johns and Bob’s former wife, Susan Weil.”

– Leo Steinberg, quoted in Encounters with Rauschenberg (1997)

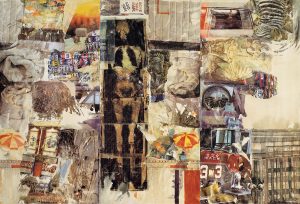

Combines are ingenious in their use of everyday objects such as neckties, umbrellas, alarm clocks, fans and anything else that captured his interest. It is the was they are put together in unlikely combinations that makes them special. Perhaps the most famous work, Monogram (1955-59) “combines oil, paper, fabric, printed paper, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe heel, and tennis ball on canvas with oil and rubber tire on Angora goat on wood platform mounted on four casters.” A favourite of mine is Gift for Apollo (1959) with a bucket chained to a wheeled object. The green necktie is a lovely touch.

- Gift for Apollo 1959

- Almanac 1962

- Pelican 1963

- Tracer 1963

- Oracle 1965

For the performance Oracle (1965), in collaboration with engineer Billy Klüver, Rauschenberg produced a group of movable objects exploring human movement interacting with these objects. 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering (1966) followed. Its success led to the project ‘Experiments in Art and Technology’ (E.A.T.) a non-profit foundation promoting interaction between artists, engineers and industry. Further experiments with technology led to Mud Muse (1968-71), an ambitious feat of engineering in which the natural springs and geysers of Yellowstone National Park were his inspiration.

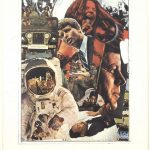

This was the time of American involvement in the space race. Technological advancement was progressive and exciting. Rauschenberg was asked to create a drawing for Moon Museum (1969), a microchip with artworks by 6 prominent artists of the time which would be sent to the moon. He was even invited to attend the launch of Apollo 11 — an exhilarating experience.

- Mud Muse 1968–71

- Signs 1970

- Glacier (Hoarfrost) 1974

- Pilot (Jammer) 1976

- Balcone Glut (Neapolitan) 1987

Parallel to this euphoria, was also disillusionment. The assasinations of Teddy Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the war in Viet Nam — the fight for Civil Rights at home contributed to Rauschenberg leaving New York and establishing his studio on Captiva Island, Florida. The 70s saw the Hoarfrost Series of sovent transfers and the Jammer Series using coloured silks found in his travels to India. It is undoubtedly this sequence of events that prompted Ruschenberg to reach out to humanity, in his way, as an artist.

“The Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange was an expression of Rauschenberg’s commitment to human rights and freedom of artistic expression. Through the R.O.C.I. project Rauschenberg travelled widely, often visiting places where artistic experimentation had been suppressed. He showed his own artwork, while exploring local art-making, aiming to spark conversations and create mutual understanding through creative processes.” (From Rules of Rauschenberg. Text by Kirstie Beaven & Lily Bonesso.) The R.O.C.I. went from 1984 to 1990. In this time Rauschenberg travelled to the 10 countries Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, the USSR, Malaysia and Germany. The project ended at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Another work also presented in China in connection with the R.O.C.I. is Glacial Decoy (1979) a dance theatrical collaboration with choreographer Trisha Brown. The backdrop, a cycling projection on four larger-than-life screens of Rauschenberg’s black and white photos of Fort Myers, Florida.

In 1985 Rauschenberg travelled to his home state Texas. The oil crisis left behind metal signs, oil cans and other metal objects from which he created the Glut Series. It is especially the white piece Balcone Glut (Neapolitan) (1985) that makes an impression on me.

Late works by Rauschenberg focus on photography and the technology of ink-jet printing. Thanks to a team of assistants he was able to produce large scale images, many referring back to or using motifs from the past as seen with the x-ray image of himself in Mirthday Man (1997) made on his 72nd birthday.

Even after 2 strokes, Rauschenberg went on, with the help of friends, to produce works from his vast achive of images. He continued looking and living until 2008.

In conclusion, a very fitting statement at the end of the retrospective exhibition: “… Throughout his collaborative, generous and experimental approach to art-making, he anticipated the social, tramadol online, networked and media-driven culture of today.”

For anyone who missed the retrospective at the Tate Modern but would still like to see it, it will start in May at the MoMA in New York City. If that is too far away, here are a couple of links giving indepth info on the artist:

http://www.tate.org.uk/rules-of-rauschenberg/

http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist

Esther Boehm

Artwork © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation